It has been eighteen months since we explored the Health of Hard Science Fiction in 2015 (Short Fiction), so we're overdue to take a look at 2016. This report divides into three sections:

It has been eighteen months since we explored the Health of Hard Science Fiction in 2015 (Short Fiction), so we're overdue to take a look at 2016. This report divides into three sections:- A selection of 42 of the best hard SF stories of 2016 together with links to the ones that are free online.

- A list of 21 controversial SF stories of 2016, where RSR disagreed with other reviewers.

- A detailed analysis of hard SF in 2016 with charts and graphs.

Recommended Stories

These are hard SF stories that were recommended by at least one major reviewer and were not recommended against by RSR, meaning we rated them ★★★★★ Award-Worthy or ★★★★☆ Recommended or ★★★☆☆ Average. We've separately included a list of "controversial stories," which were recommended by other reviewers but which RSR recommended against. There are 27 stories free online (click to highlight).

Controversial Stories

These stories earned recommendations from one or more reviewers and yet Rocket Stack Rank recommended against them, meaning we rated them ★★☆☆☆ or ★☆☆☆☆. We know that readers have different preferences, which is why we link to reviews from other reviewers in the first place. By listing these "controversial" stories, we hope to make it easier for readers whose tastes are very different from ours to find reviewers who are more to their liking. We still encourage such readers to use RSR, of course; they just need to pay attention to the "Recommended By" lines and ignore the star ratings.

Analysis

For this analysis we wanted to answer the following questions:

- Is Hard SF really rare?

- Do reviewers dislike hard SF?

- Where is the best place to find it?

- When and where do hard SF stories take place?

- Are hard SF stories depressing?

If you can't wait, you can skip the analysis and jump straight to the conclusions.

Counting

Except where otherwise indicated, we have counted words, not stories. So in the charts below, a 40,000-word novella will count eight times as much as a 5,000-word short story.

Sources: Where Did the Stories Come From?

In 2016, Rocket Stack Rank read and reviewed 814 works of short science fiction and fantasy comprising 5,762,246 words. These included

- Every story (598) in the eleven most important SFF magazines, of which

- 252 were from the four print magazines.

- 346 were from the seven main online magazines.

- Every story (158) in eleven key SFF anthologies.

- Twenty-eight stand-alone novellas, including all 24 from Tor.

- Thirty stories from various other sources. Generally, these were stories that appeared in big "best of the year" anthologies, were nominated for awards, or otherwise got special attention.

Read our submission criteria to see how we picked these sources. We think they represent the vast majority of good original science fiction and fantasy published in 2016.

In terms of word counts, the breakdown is about one-third print magazines, one-third online magazines, one-sixth anthologies, one-sixth novellas, and a tiny amount from elsewhere.

To get an idea of what we might have omitted, have a look at all the SFWA-qualifying publications and the Semiprozine Directory.

Quality: What is a "Good Story?"

We used the same definition that we did for evaluating SFF short-form editors: we took our recommendations together with those of six prolific reviewers of short science fiction and fantasy and we divided all works into three categories: Recommended, Ordinary, and Not Recommended. By this measure, 44% of all the stories RSR reviewed in 2016 were recommended. Again, this includes reviews from other sources; Rocket Stack Rank only recommends 18% of the stories we review.

When we look at Hard SF alone, this drops to 38% recommended, which is still quite a lot. Reviewers might be a little harder on Hard SF, but not much.

Genre Definitions

Hard SF

For 2015, we required that "the science must be accurate enough that an educated layman does not have to suspend disbelief for it." With the perspective of 18 months, we've decided that's too strict; by that definition, "I, Robot" wouldn't be hard SF, since "positronic brains" make no scientific sense. It also ruled out the possibility of there being bad hard SF due to incorrect science, since the old definition required good science for a story to be hard SF at all.

Instead, we've adopted the rule that in a hard SF story, details of the science/technology are key to the plot, and the story creates the impression that there is a scientific explanation for everything that happens. This allows us to class "I, Robot" as hard SF as well as identifying a class of bad hard SF where the poor science breaks suspension of disbelief.

Soft SF

This replaces our previous "situational SF" category. These are stories where the science/technology isn't central to the plot and generally isn't explained at all. Soft SF stories do create the impression that everything has a scientific explanation though; there are no appeals to the supernatural.

High Fantasy

Any story set in a secondary world that isn't derived from our world we classed as High Fantasy. This includes both Epic Fantasy, where great affairs of kings and queens are involved, and Sword and Sorcery, which focus on more ordinary individuals in such worlds.

Low Fantasy

Stories with supernatural elements that are set in our world or in some variation on our world we classed as Low Fantasy. This includes Urban Fantasy, Slipstream, vampire and zombie stories, Cthulhu stories, and Steampunk. This is where we've put Alternate History as well.

Mixed

Only a handful of stories didn't fit into one of these four categories, generally because they started off as SF but then introduced the supernatural later on.

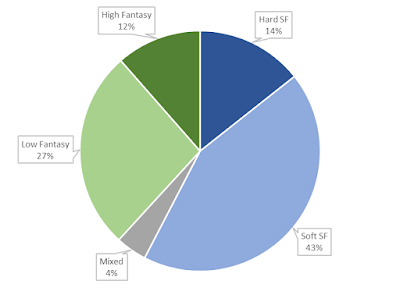

Even with the different definitions, the division is remarkably similar to the numbers for 2015. We get 14% hard SF vs. 12% last year, and 57% total SF vs. 57% last year. With that caveat, it's safe to say that hard SF certainly doesn't seem to be dying.

Recommended Hard SF

From here on, except where stated otherwise, we'll only be discussing recommended hard SF, which means those hard SF stories which fell into the "recommended" quality category. There are 42 such stories, comprising 278,801 words--about the length of a giant novel like Seveneves.

Genre Breakdown

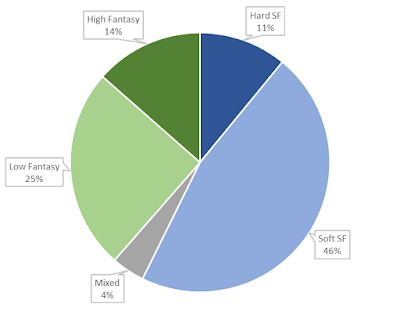

There's not much difference in the genre breakdown for recommended stories, but we'll show it because it lets us answer two questions.

Second, we can directly compare this chart with last-year's chart, and we can see that, despite the definition change, the numbers are almost the same. If hard SF is dying, it isn't dying fast enough for us to notice a difference from one year to the next.

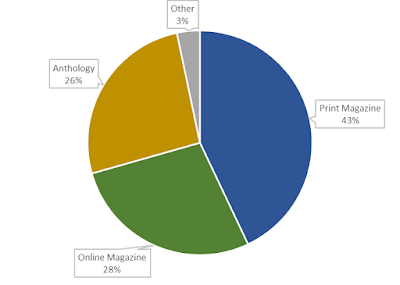

Sources

The sources for recommended hard SF are very different from the sources for speculative fiction in general. Roughly half comes from the old-fashioned print magazines and the rest is split between online magazines and anthologies.

When we look at the number of stories involved and compare that with last year's chart, we can see that there isn't actually a lot of change compared with 2015.

When we look at the number of stories involved and compare that with last year's chart, we can see that there isn't actually a lot of change compared with 2015.

Analog and Asimov's ran more good hard SF stories than anyone else, although they swapped places this year. Everyone else had just one to three good hard SF stories for the year.

Magazines

Of the eleven magazines, only nine published any recommended hard SF in 2016. (The other two were Beneath Ceaseless Skies and Apex.)

Analog and Asimov's accounted for almost half of all the recommended hard SF in 2016 that appeared in the eleven magazines we followed.

Analog and Asimov's accounted for almost half of all the recommended hard SF in 2016 that appeared in the eleven magazines we followed.

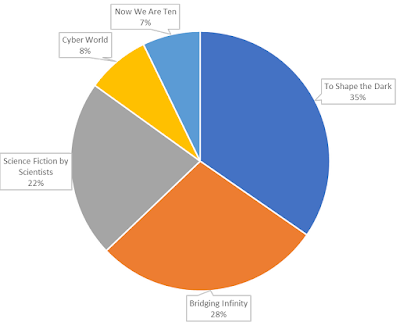

Anthologies

Two anthologies, To Shape the Dark and Bridging Infinity accounted for most of the good hard SF in the anthologies we reviewed in 2016. Science Fiction by Scientists came in a bit behind those two, and the three accounted for over 80% of recommended hard SF published in anthologies in 2016.

Novellas

Not a single stand-alone novella was hard SF--recommended or not. A number were soft SF though.

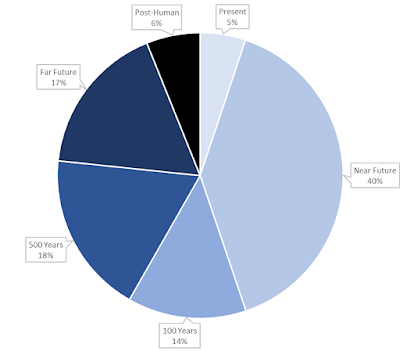

Distribution in Time

Hard SF stories usually take place in the future, but it's interesting to look at how far in the future. Many stories give exact dates. Others imply a date range from the ages of the characters and events they've witnessed. Lacking any of that, we used clues like technological/social/environmental changes.

Here's the list:

Here's the list:

- Present: a story where one could imagine the events taking place as we speak. That means no technological, political, or environmental changes from today.

- Near-future. Less than 100 years from now. Only changes within the range of what we see in scientific articles.

- 100 to 500 years. Anything with routine interplanetary travel wound up in this bucket, lacking any specific dating. Likewise anything with deeply flooded major cities.

- Over 500 years. Anything with interstellar colonies went here, provided they still remembered what Earth was, and provided humanity hadn't evolved at all.

- Far Future. Any story where humanity had changed in nature either through evolution or engineering, or, which was so far in the future that humanity had forgotten where it came from.

- Post-human. Stories set after the extinction of the human race.

Whenever a story covered multiple time periods, we labeled it according to when the majority of the action took place. We excluded two stories which involved no human beings at all for which it was impossible to make any estimate of date.

Near-future stories are surprisingly popular, but it's arguable that it's hard to write a convincing hard SF story that uses technology that hasn't even been thought of yet.

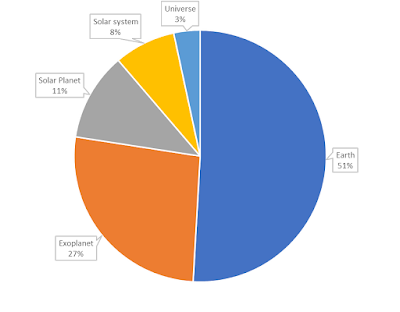

Distribution in Space

Just as interesting as when stories take place is where they take place. We divided the story locations into five categories:

- Earth. (Includes low Earth orbit.)

- Exoplanet. (Orbits another star.)

- Solar Planet. (Planet or asteroid in our solar system. Includes the moon.)

- Solar System. (Action takes place in transit within our solar system.)

- Universe. (Action takes place in transit between stars.)

When a story involved more than one location, we picked the one where most of the story took place, if possible.

Over half of all hard SF takes place here on Earth. It's not in the chart, but two-thirds of stories set on Earth are within 100 years from now.Surprisingly (to us, anyway) exoplanet stories are more popular than stories exploring our own solar system.

Optimism

People often complain that SF is gloomy these days, but that doesn't seem to hold true for the recommended hard SF stories.

- Optimistic means the story ends on a positive note. The good guys win.

- Neutral means there was a mixed result. The good guys win, but at a heavy cost.

- Pessimistic means the story ends on a negative note. The good guys lose.

We tracked humor and horror as well, but neither was common enough to include in the chart.

One caveat is that this is a little "neural-heavy" because it counted stories where the characters had a hard struggle but achieved a happy ending as neutral, not optimistic. The 2017 numbers will likely be more optimistic. The stat that only 1/5 of recommended hard SF stories are pessimistic is pretty solid though.

Conclusions

- Hard SF is about a sixth of all speculative fiction, so it's not rare.

- Reviewers recommend hard-SF stories at about the same rate that they recommend other stories, so there's no clear bias against hard SF.

- People who like hard SF should seriously consider subscribing to the print magazines and picking up two or three anthologies per year.

- About half of hard-SF stories take place here on Earth in the near future. The rest are all across time and space.

- Only about a fifth of hard-SF stories have a negative tone. There are more optimistic than pessimistic hard-SF stories.

In summary, we'll repeat our conclusion from last year: it's hard to tell whether hard SF is changing, but it certainly seems to be in much better health than some people think.

No comments (may contain spoilers):

Post a Comment (comment policy)